3 School Metrics

3.1 How do training schools compare on student outcomes?

For the vast majority of students, ballet training does not lead to a sustained career as a professional dancer. To have a chance at a professional career, you likely have to do at least one of these three things: 1. Go to multiple summer programs, 2. Attend a training program in a major metropolitan city, or 3. Leave or reduce regular school to train.

Any single one of these tasks is a huge commitment – emotionally, physically, and often financially. And naturally you want to increase your odds of a career by choosing the right program. So what metric would indicate a quality program to you?

3.1.1 Signs of Quality

Interpret with caution: Some company bios do not list full training data, potentially biasing the results for some schools. We do not currently have class size information and cannot adjust for it at this time.

While finding students employment should be a goal for many ballet schools, this is not the only valuable aspect to consider when choosing a school. Schools are not superior or inferior simply based on their ranking in a metric we report. There are many factors besides the quality of students that impact eventual employment in the companies we study.

Members of the team attended these schools in the past: HARID Conservatory, Butler University, School of Richmond Ballet. This had no effect on lists.

For the 2022 - 2023 Season, there were 1056 total dancers, with complete information for 1008 individuals (95.5%). Many of the dancers with missing information are from Sarasota Ballet and Ballet West, as those companies do not publish full biographies for all of their dancers. We also did not include New York City Ballet apprentices in the analysis, as they are technically part of the school.

Here are the lists:

Our data for non-binary dancers is currently incomplete. A table for schools attended by non-binary dancers will be included with the update to next season’s data.

The first thing to point out is that some dancers attend multiple schools – these dancers add one to the tally for each school attended. Overall, 787 unique schools trained a dancer in the top 26 companies during the 2022 - 2023 season analysis. (In the 2018–2019 season, 388 schools trained dancers in the top 7 companies. In the 2020–2021 season, 715 schools trained dancers in the top 26 companies.)

We have included metrics related to quality. We have listed the percentage of alumni in one of the seven largest US companies and the percentage of alumni above the rank of corps de ballet. This allows us to examine the “prestige” of training at each school.

We notice that the top spots on our training schools list are dominated by “affiliate schools” – these are schools that have direct ties to professional companies. Based on our past post looking at affiliate school hiring, we know that certain companies (especially New York City Ballet) heavily emphasize hiring graduates from their affiliate schools. However, some of these affiliate schools appear to do well in placing students in top companies overall – not just in the affiliated company. The hiring of students who trained at affiliate schools into main companies is explored in our later section “In-house Hiring.”

Then, we have the non-affiliated schools. We have recognizable names on this list: the Rock School, Royal Ballet School, HARID Conservatory, Cuban National Ballet School, Kirov Academy, and University of North Carolina School of the Arts. These schools have lower numbers of alumni dancing in the largest 26 companies, but they are still capable of competing with some of the affiliate schools like Boston Ballet. In our previous analysis on training schools for dancers in the top seven companies, Royal Ballet School and Paris Opera Ballet School were the only foreign schools on these lists. Now we see that Cuban National Ballet School produced several high-ranking dancers who are not in the top seven but instead in the top 26 companies. We know that dancers born in the UK or Cuba are not particularly common in the top seven American ballet companies. It seems the Royal Ballet School heavily recruits internationally-born students, explaining this finding.

Comparing the male and female training lists, we notice discrepancies. For example, the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School associated with American Ballet Theatre seems to place more of the women they train in then top seven companies than the men (68.4% women to 54.5% men). Furthermore, international schools are more likely to be toward the top of the ranking for male training. Past analysis found that male dancers in the top seven companies were more likely to be born outside of the US than female dancers, which we attributed perhaps to the quality or quantity of male training in the US. The main takeaway from these two lists are that the quality of male and female training at top schools may differ – something to keep in mind as you choose schools.

3.1.2 Finishing School

Training a student for just one year before they find professional employment in a company is different than training a student for several years. We don’t necessarily have the data to distinguish these two scenarios, but we can compare our list above with a list of the top “finishing schools.”

We define a finishing school as the last school a dancer attended before joining a main company or second company program. We will call dancers who exit these schools to launch professional careers “graduates.”

We see some major changes to this list. It seems that many dancers who attend nonaffiliated schools decide to switch schools before graduating. This supports the concept of a finishing school, often chosen as much for proximity to a professional company as for the quality of its training. The last year of school is a critical period during which the student has to translate their training into either a main company, second company, or professional division contract. Affiliated finishing schools have a major advantage in terms of pedigree and proximity, resulting in a greater chance to be noticed by artistic staff in one of these top companies.

3.1.3 Conclusion

None of these metrics means that the quality of training at schools absent from these lists is inferior. These lists only state the most common pathways to top companies – something directly affected by the influence of major ballet organizations.

There are a couple of things these lists don’t account for. One is class size. Class size is tricky – too big and the level of individual attention goes down, but too small and the raw number of graduates seeking jobs decreases. Two is coaches. Some dancers have personal coaches who are hugely influential on their training. Our analysis attempts to account for coaches, but naming people in dancer biographies is not a common practice. Three is missing information on dancers. This might have lowered several schools’ positions. Many of the dancers with missing training information were dancing at Sarasota Ballet or Ballet West – a potential source of bias.

3.2 For each school, what are the companies and ranks of alumni?

This breaks down the combined data we saw above into specific companies and ranks. We then get a sense of how training schools place their dancers. The below data is for the last season only (2022 - 2023).

Again, there may be missing dancers due to late updating of company websites or missing training information from biographies, contributing to inaccuracies for specific schools.

3.2.0.1 Number of Dancers in Each Company By Training School (Last Season Only)

Type in the school selection box after clicking it to search for specific schools. Shift + click to view multiple schools:

3.3 For each season, where did newly joining dancers train?

Or stated another way: how many dancers from each school join top companies each season?

As dancers graduate from training schools, some of these dancers find positions at main companies or second companies. Looking at the training history of newly joining dancers each season, we get an estimate of how many students from the graduating class go on to join these companies. As the vast majority of newly graduated dancers join their first company as apprentices or corps members, we can focus on these ranks. By dividing this number by the size of a school’s graduating class size (we do not have this data), we also get a rough estimate of the chances of finding a job at one of the companies we study for each graduating class.

Dancers who have recently joined companies frequently do not have updated biographies on company websites. We collect our data on January 1st each season; however, there may still be missing data due to this.

3.3.0.1 Number of Dancers Newly Joining Each Company Per Season By Training School

Type in the school selection box after clicking it to search for specific schools. Shift + click to view multiple schools:

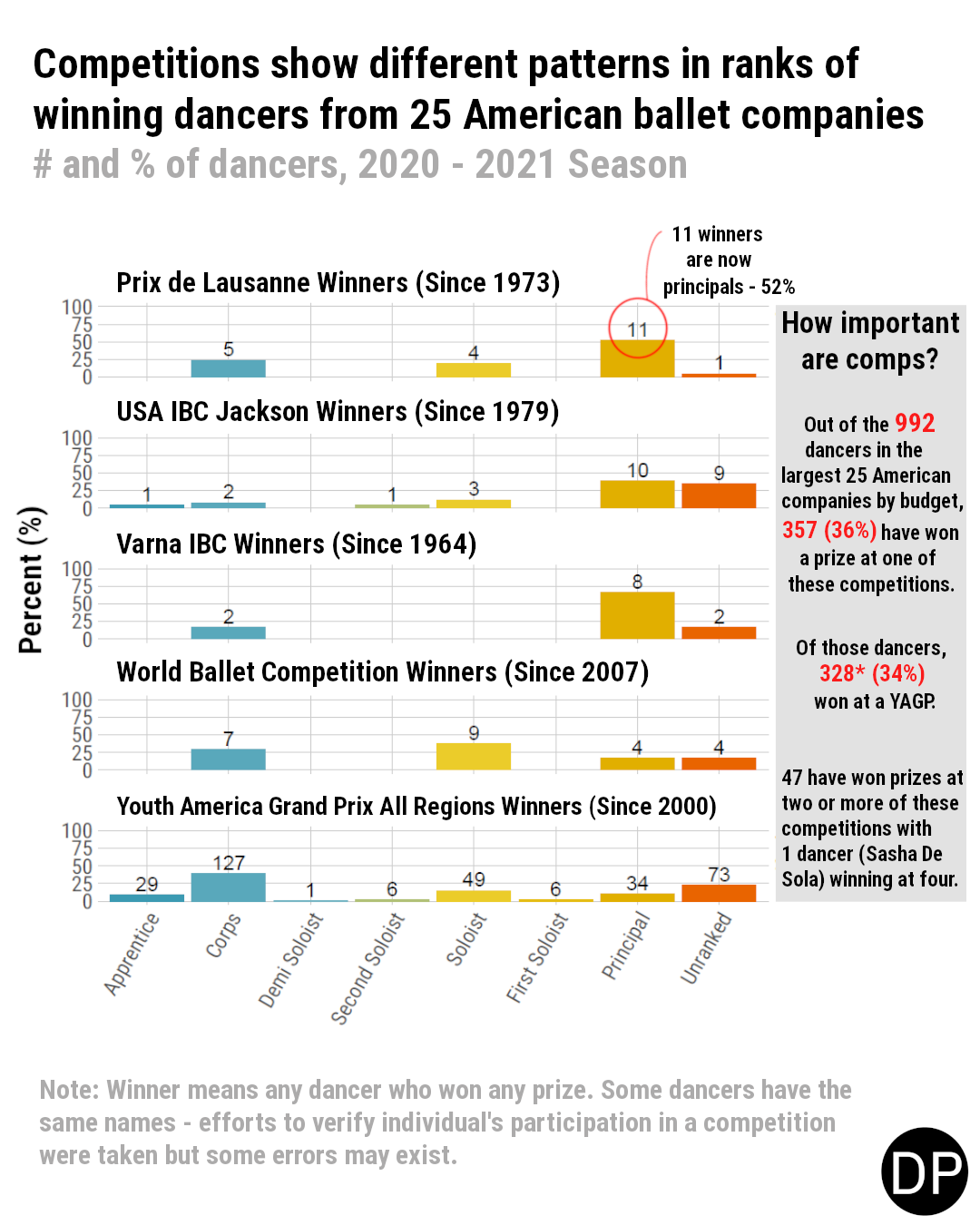

3.4 How common is competing in competitions for professional dancers in the US?

We currently only have this data for the 2020-2021 Season for 25 companies.

3.5 How successful are college programs at placing dancers?

As mentioned in the Introduction, many working dancers do not complete a college degree before joining a company. While a college degree is certainly not necessary to work as a ballet dancer in the US, dancers may feel they need further training or want to pursue a degree unrelated to dance.

The Dance Data Project® released a report in February 2022 that includes a relatively comprehensive list of universities that have a dance program.